FIRST LINE

Life is full of opportunities.

FROM THE BLURB

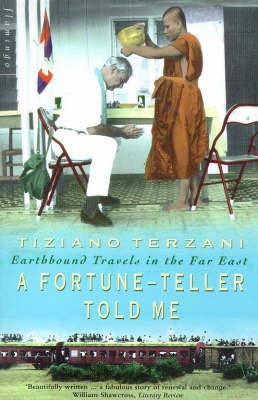

Warned by a Hong Kong fortune-teller not to risk flying for a whole year, Tiziano Terzani—a vastly experienced Asia correspondent—took what he called ‘the first step into an unknown world’ … Travelling by foot, boat, car and train, he visited Burma, Thailand, Laos, Cambodia, Vietnam, China, Mongolia, Japan, Indonesia, Singapore and Malaysia. Consulting soothsayers and shamans wherever he went, he grew to understand and respect older ways of life and beliefs now threatened by the crasser forms of Western modernity.

A FORTUNE-TELLER TOLD ME

Tiziano Terzani spent the whole of 1993 grounded, but he let that affect neither his work nor his wanderlust. As a foreign correspondent for Der Spiegel in the vast continental landmass of Asia, that was no small achievement. But A Fortune-Teller Told Me is far more than a series of despatches from the East, and more too than a simple travelogue of loosely-connected terrestrial journey.

The first passage I’ll pull out is a knockout body-slam on air travel—this from a man who adored being a traveller so much that he once said he wanted it the only word on his gravestone besides his name.

Reached by plane, all places become alike—destinations separated from one another by nothing more than a few hours’ flight.

Frontiers created by nature and history and rooted in the consciousness of the people who live within them, lose their meaning and case to exist for those who travel to and from the air-conditioned bubbles of airports, where the border is a policeman in front of a computer screen, where the first encounter with the new place is the baggage carousel, where the emotion of leave-taking is dissipated in the rush to get to the duty-free shop-now the same everywhere ...

It’s clear from Terzani’s passion that air travel is not what would earn him that gravestone honorific ‘traveller’. As someone who has only taken one return flight since January 2010, but who often struggles to put into words precisely why—this is it.

Nowadays airports have the false allure of advertisements—islands of relative perfection even amid the wreckage of the countries in which they are situated …

A railway station, on the other hand, is a true mirror of the city in whose heart it lies.

You can change the shadows

As you might have guessed, Terzani’s preoccupation in both book and flightless year was prophesy. Why do we seek our fortunes? And how have we soothed our inflamed fears for the future? For millions, for millennia, the answer was—and still is—found in the occult.

Often dismissed out-of-hand by intellectuals, Terzani finds the best fortune-tellers are shrewd judges of humanity, experienced psychologists who really can help their clients make sense of the chaos.

Reaching London after a long train journey across the entire continental plate, Terzani consults a fortune-teller called Norman. Asked whether he really believes in the prophesies of the cards, Norman explains:

‘The cards read the shadows of things, of events. What I can do is help people to change the position of the light, and then, with free will, they can change the shadows. That I really do believe: you can change the shadows.’

Most of the fortune-tellers Terzani visits suggest specific ways that he can counteract any bad news they have foreseen: these are known as ‘merits’, usually small donations, the purchase of amulets or the burning of incense.

Fate is negotiable; you can always come to an agreement with heaven.

Rhyme is consoling

As the year wears on, Terzani is surprised less and less by the startling accuracy of some of his fortune-tellers predictions. He notices the role that he is playing in the game:

[A fortune-teller] has no sooner spoken than we are racking our brains to find something in our experience to match his words. And in this there is pleasure, as there is in writing poetry. Suddenly life seems to become poetry because of some rhyme that makes sense of the facts, and bestows an order upon them. Rhyme is consoling.

But Terzani rarely condescends to his fortune-tellers. There is little remaining of the hard-nosed cynical journalist who saw the fall of Saigon in the 1970s. If there is pleasure in seeking one’s fortune and if the rhyme one finds is consoling, then why condemn the cure?

We ourselves give the answer

Terzani finds that fortune-telling and overland travel are rhyming partners, as he seeks the meaning of his dozens of prophecies.

It seemed to me that the point of travelling is in the journey itself, not in the arrival; and similarly in the occult what counts is the search, the asking of questions, not the answers found in the cracks of a bone or the lines of your palm. In the end, it is always we ourselves who give the answer.

This cuts the Gordian Knot of free will versus fate: are we captains of our own ship or are we wholly at the mercy of the wheel of fortune? The answer to this question, Terzani decides, is yes.

[T]here is no solution to this problem of fate … Either you can see life as being written somewhere in advance, or you can see it as being written by you every minute as you go along. Both versions are true. Every decision can be seen as either a free choice or a product of predestination.

Terzani realises that the Ancient Greeks knew this thousands of years ago. We’re still struggling to catch on to the message contained in the story of Oedipus, which Terzani says ‘lies at the very roots of our culture’.

King Laius left his baby son to die on a mountainside after hearing a prophesy that this child would grow up to kill his father and marry his mother. But a kind shepherd took pity on the boy, Oedipus grew up not knowing his real parents and… As you can see:

If Laius had ignored the fortune-teller, nothing would have happened; the prophecy is fulfilled precisely because he takes it seriously and does his best to avoid the consequences. So fate is ineluctable, and the prophecy is part of it: it precipitates events which men, left to themselves, would never choose to bring about.

The owner of the Nagarose

During his flightless year, Terzani takes a cruise with his friend Leopold on a commercial shipping liner called the Nagarose, owned by an anonymous American.

They don’t have tickets for the journey, organised through friends of friends in Italy. They have all the freedom of the ship, but none of the responsibility. This makes Leopold laugh:

‘Just think of that American who says: “I am the owner of the Nagarose.” He’s maybe never set foot on it, and spends all his time in an air-conditioned office sorting out problems of insurance and sugar-loading. And you and me? Here we are enjoying his ship!’ said Leopold.

Sometimes in capitalism we get caught up in ownership instead of enjoying the fruits of the earth. What if we already have everything we need? What if everything we need is simply out there, waiting to be, not owned, but shared.

The idea that the American had only a piece of paper declaring him to be the ship’s owner, while we, without even a ticket, had the run of it, made me laugh too. ‘In life one should always be as on this ship: passengers. There is no need to own anything!’

Obnoxious memory

Memory can be a wonderful refuge, and if I ever live to be old, as the fortune-tellers predict, I shall enjoy rummaging around in it as in an old family chest forgotten in the attic; but it can also be a terrible burden, especially for others.

These are Terzani’s reflections as he walks through Ho Chi Minh city in Vietnam—where decades earlier he’d witnessed the triumph of the revolutionary forces of the Vietcong in the fall of Saigon. The American War was over. A new society—a new state was born. But its leaders found it impossible to fulfil the promises they’d made in the jungle.

As I walked, constantly haunted by one recollection or another, I realised how obnoxious I was with this memory of mine: obnoxious to people of my own age, because my memories of the past made it hard for them to lie about promises that were made and not kept; obnoxious to the young, who live in the present and do not want to hear about the world of yesterday. I was obnoxious, but at least harmless.

Terzani calls foul on those leaders—those promises made that he inconveniently remembers. But his obnoxious journalist’s memory is nothing compared to those still living whose very existence is a painful reminder for a Vietnamese society that would rather forget.

In that war I had lost only some illusions—a loss that was not even visible. But what about those who in that revolution—a failed revolution, like all the others—had lost legs, arms, eyes, or even just their youth, and who now dragged themselves around the streets, begging?

They were really obnoxious, with their memories so physical, so visible, such a burden for everyone.

Terzani wasn’t alone in mourning the forgotten promises.

A man who had been a mythical figure in the Vietcong told me the tragedy was that they had won the war: losers are forced to adapt, to change, and thus to improve; but winners think they have nothing to learn.

Every place is a goldmine

As a writer myself, and in the spirit of ‘books make books’, I enjoyed the insights into Terzani’s writing process. Or perhaps it’s more a voyeuristic observational style. Or maybe even simply a demotic way of life.

Every place is a goldmine. You have only to give yourself time, sit in a teahouse watching the passers-by, stand in a corner of the market, go for a haircut. You pick up a thread—a word, a meeting, a friend of a friend of someone you have just met—and soon the most insipid, most insignificant place becomes a mirror of the world, a window on life, a theatre of humanity.

Coconut pearls and dog’s teeth

Terzani meets a man who wears a coconut pearl around his neck. The man informs him that they are exceedingly rare:

‘For every ten thousand coconuts, there’s one that has a pearl inside.’

After modest research, I’m sorry to say that this romantic botanical gemstone is most probably mythical. But why let that ruin the man’s veneration of his necklace? Terzani offers us this Tibetan proverb:

‘If there is veneration even a dog’s tooth gives forth light.’

After all, nothing

In 1975, Terzani was a witness as Pol Pot’s Khmer Rough took Phnom Penh, the capital of Cambodia. Mistaken for the wrong sort of foreigner and facing a firing squad, somehow his luck held. In 1993, he travelled back to the country.

In Poipet the taxi set us down in the market square. I instinctively went to see the wall against which the Khmer Rouge had put me in April 1975. I stood there a few minutes in silence, as if it really were somebody's tomb. I thought of the many things that had happened to me since, of the many places I had been, the people I had known, the countless words I had written. I thought of all the things I would not have done had my life ended there—so much, and after all, nothing.

The fortune-tellers Terzani consulted throughout 1993 were wrong: he did not live into old age. He died in 2004, aged 65. So much, and after all, nothing.

Hearing silence

Terzani ends the book at a retreat, learning how to meditate from an American ex-spy.

This silence was a great discovery. Without the foreground of other people’s words, I realised that the glorious beauty of nature was in its silence. I looked at the stars and heard their silence; the moon made no sound; the sun rose and set without a whisper. In the end even te noise of the waterfall, the bird calls, the rustle of the wind in the trees, seemed part of a stupendous, living, cosmic silence which I loved and in which I found peace.

This discovery appals Terzani. As the book began with a rage against vapid air travel, so it ends with a rage against the ceaseless noise of modernity.

It seemed that this silence was a natural right of every man, and that this right had been taken from us. I thought with horror of how for so much of our lives we are pounded by the cacophony we have invented, imagining that it pleases us, or keeps us company. Everyone, now and then, should reaffirm this right to silence and allow himself a pause, some days of silence in which to feel himself again, to reflect and regain a degree of health.

Amen.

LAST LINE

After all, one is always curious to know one’s fate.

WHERE NEXT?

Terzani references Thornton Wilder’s 1927 novel The Bridge of San Luis Rey, in which a monk tries to figure out why God would have arranged for five strangers to die together thanks to the apparently pointless collapse of the titular bridge.

Wilder’s novel was also an inspiration for one of my favourite novelists, David Mitchell, so that’s what I’ll be reading next. On eBay I had a choice between paying £2.85 for an edition published by Penguin in 2001 or paying triple that for another Penguin published in the early years of World War II. I couldn’t resist.

If you’ve read an amazing book you think I should read, please reply to this email or add it to the ‘What should I read next?’ thread, where you can see other people’s recommendations too.

END MATTER

Recommended by MC from the home library

370 pages, ~200,000 words

Read: 30 June to 10 September 2020 (including a six week cycling hiatus)

ISBN: 9780006550716

This newsletter review is published under the ‘fair dealing’ copyright exemption for criticism, review or quotation. If you’ve enjoyed this newsletter, please consider buying the book: Waterstones // eBay // Find your local bookshop

CREDITS

David Charles wrote this. He publishes another newsletter about the overlooked corners of our world called, humbly, The David Charles Newsletter. David is co-writer of BBC Radio Wales sitcom Foiled, and writes for The Bike Project, the Center for International Forestry Research and Thighs of Steel. He also edits books about adventure and activism. Reply to this email, or discover more on davidcharles.info. Thank you for reading!